It ain’t what you know that gets you into trouble.

It’s what you know for sure that just ain’t so.

Mark Twain

Part 1 of 3

Beware the Fundamentalist Narrative

“One of the uses of history is to free us of a falsely imagined past. The less we know of how ideas actually took root and grew, the more apt we are to accept them unquestioningly, as inevitable features of the world in which we move”

Robert H Bork, The Antitrust Paradox(1993)

“Frydenberg exhumes Thatcher and Reagan”, so the Murdoch press gleefully extols.

A critique in three parts –

1. Beware the ‘fundamentalist’ narrative

2. The growth of inequality, ideological crusades and zombie economics

3. Keynes, Piketty and the Pope identify the hegemonic issue

When Josh Frydenberg invokes Thatcher and Reagan as some sort of template for post-pandemic economic recovery in Australia, he is either profoundly ignorant or he gives excessively more credit to Reagan’s rhetoric than he does to historical facts.

Reagan’s vocal hostility to government was legendary – “the most terrifying words in the English language are ‘I’m from the government and I’m here to help’.” – though trite, it does capture the essence of what proved to be a Reagan fantasy. Despite the rhetoric he was the highest spender of US Presidents since FDR during the Great Depression!

But initially it’s worth discussing what we understand by “government” and the “state” which are frequently used interchangeably. In Anglo America (and their ex-colonies) Australia and Canada, the ‘state’ is typically understood as a sovereign entity and provides a neutral arena of discussion, involving elected representatives who meet and debate and supposedly reflect public preferences that fall within the Overton Window – a model for understanding how ideas in society change and influence politics over time. The ‘government’ is the particular group of people that controls the state apparatus and defines what public preferences become policy at a given time. Under the ‘separation of powers’ doctrine, the ‘executive’ branch is essentially the “government” of the day.

Underlying such pluralist political theory is a belief in majoritarian electoral democracy – which attributes government policies to the collective will of the average citizen or ‘median voter’ empowered by democratic elections.

The validity of this conventional view was tested a few years ago by two eminent US academics (Gilens & Page 2014). In a well-publicized study, Gilens and Page argue that economic elites and business interest groups exert strong influence on government policy while ordinary citizens (the median voter) have virtually no influence at all.

Their main findings of the research are that “economic elites and organized groups representing business interests have substantial independent impacts on government policy, while average citizens and mass-based interest groups have little or no independent influence.”

Although this was a major American study, it is probable that a similar pattern of results would be found here. Importantly, it illustrates the reality of the ‘state’ being an entity malleable to the concerns of powerful special interests and lobby groups.

In view of the eminence showered on this duet in politically conservative circles, it would be quite instructive to explore the actual genealogy of Frydenberg’s captivation by the Thatcher and Reagan legacy.

Given the synchronicity of their respective governments in the late seventies/early eighties – one could speculate whether it was an inevitable social conjunction or simply random – a chance moment when economics engaged politics? As we later discovered, this ill-fated congruity gave rise to significant social dysfunction in the Anglo-America states for nearly half a century.

But initially we should examine the extent of public sector intervention in the economy. Typically, the public sector is measured in terms of government expenditure (sometimes tax revenue) as a proportion of GDP. The metric is crude and not precise but is widely accepted and indicative as a measure of the size of government. Let’s examine the reality not the rhetoric –

United Kingdom

Government Spending to GDP in the United Kingdom averaged 39.87% from 1956 until 2021, reaching an all-time high of 54.40% in 2021 and a record low of 34.50% in 1989.

United States

Government Spending to GDP in the United States averaged 37.20% from 1970 until 2020, reaching an all-time high of 44% in 2020 and a record low of 33.4% in1973.

Australia

In the four decades after Gough Whitlam expanded the size of government in the early 1970s, the level of expenditure has remained largely unchanged at an average of about 25 % of GDP.

Empirical analysis is usually the catalyst of change in the natural sciences, social science is no exception – paradigm shifts in macroeconomic theory follow this pattern. Such shifts are not only empirically generated but are often affected by social, political, or religious convictions.

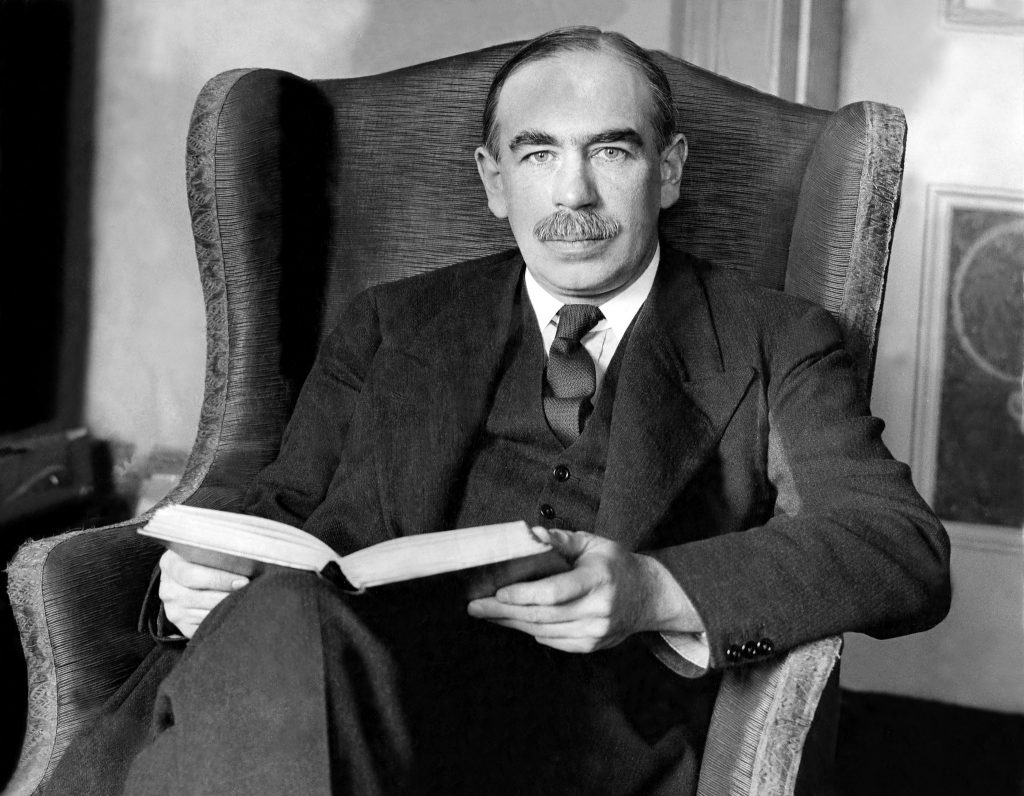

As for the evolution of post-WW2 macroeconomics, the ever-insightful Keynes did warn us –

“Practical men who believe themselves to be quite exempt from any intellectual influence, are usually the slaves of some defunct economist.”

For the past 40 or so years we have been the slaves of a not-quite-dead set of economic ideas. These ideas have shaped the way people think about the economy and had a powerful effect on contemporary politics and government policy. I refer, of course, to the resurgence of neoliberalism – the “market fundamentalist” version of capitalism.

This shift to neoliberalism was not an accident of history but the result of the coordinated efforts of an elite movement of academics organised as the Mont Pelerin Society founded in 1947 by Friedrich Hajek, Ludwig Von Moses, Karl Popper et al. The Society developed a critique of the Keynesian social democratic economy post WW2. The strategy was to provide an intellectual economic underpinning to its views and pursue the election of supportive governments. The academic component never really became completely hegemonic, the strategy was only decisive at the level of politics. It was the election of the neoliberal-influenced Thatcher and Reagan governments which gave impetus and ensured this paradigm shift in economic theory. A symbiotic triumph or a slave to some defunct economist?

This brief preamble brings us to the focus of this paper, the Thatcher/Reagan symbiosis, which became central to the imposition of their ideological world view on that perennial issue: the role of the state in the functioning of an economy. How a government coordinates or integrates the level of state intervention in the economy has massive societal implications. Unlike the UK or Australia, the very history of America where scepticism of the ‘state’ lies deep in the national character and, as recent events have shown, that government reach has proved to be extremely vulnerable with disturbing implications for the modern world.

The root of this lies in the American obsession with the ‘individual’ over the ‘collective’ – an obsession perhaps explainable by the misconception of the term “freedom”. This cultivated ignorance – ignorantia affectata – leads to the libertarian absurdities such as resistance to the wearing of masks in a pandemic. As JS Mill sets out in his treatise “On Liberty” that freedom is the accumulation of rights, and exercising choices in what to think, say, and do. However, it has never been regarded as absolute and unlimited. In fact, Mill drew a distinction between ‘liberty’ and ‘licence’. This was in recognition that liberty does not mean the licence of individuals to do just as they please, because that would obviously lead ultimately to the destruction of liberty. The essence of his argument is that the limits of freedom are reached when its exercise causes harm to others.

In Australia, citizens trust in government has been quite variable – perhaps more influenced by pragmatism than abstract principles. Surveys suggest that the range of trust has been as low as 18% but increasing to a high of over 80% during the roll-out of Jobkeeper amidst the Covid pandemic. This burst of support for government is, perhaps, best explained by the bipartisan political support that occurred and the ‘politician’ stepping back allowing ‘health science’ to take the lead in what was seen by the public as a medical issue. That of course has dramatically receded reflecting the Morrison government’s bungled vaccine rollout.

Unfortunately, this rather confused obsession with protecting the individual from the clutches of the state in the US manifests itself in one of the most significant tropes in the economics community today. A trope employed by Frydenberg to channel the (Milton Friedman inspired) Ronald Reagan assertion in his 1981 inaugural address “government is the problem, not the solution”. This view was preempted a year earlier with the arrival in 1979 of the “Iron Lady” in the UK.

The welfare state – the old social democratic consensus – introduced in the wake of the Second World War under Keynesian influence and teaching politicians that, without major government intervention, capitalism is inherently unstable and prone to delivering lengthy periods of unemployment – was gradually dismantled. The ‘anti-collective’ nature of Thatcherism – ‘there is no such thing as society’ – however, emerged as nothing more than the standard neoliberal fundamentalist playbook – deregulation, privatisation, tax cuts, spending cuts, subjugating trade unions, etc.

As observed earlier, empirical analysis is often the catalyst of change. By the late 1960s and mid 1970s a series of socio-economic events sent shock waves around Western democracies – their manifestations had far-reaching political consequences.

In the late ‘60s early ‘70s the whole picture changed as we saw the transition from the welfare state to neoliberal orthodoxy. Socially progressive values developed almost concurrently with a significant macroeconomic dilemma – a dilemma with both economic and political implications. On the world stage, we witnessed a traumatic complex of inter-related cultural and political events – anti-Vietnam rallies, rise of the ‘counterculture’, the assassinations of Bobby Kennedy and Martin Luther King Jr, the Chicago Seven trial, the Black Panthers emerged as a major social movement, the Beatles US invasion, Bob Dylan, Jimi Hendrix, protest folk music- Joan Baez/Pete Seeger, the end of the Prague Spring with the Russian invasion of Czechoslovakia, in Europe around 10 million French workers strike in support of students from the Sorbonne. Even in world backwaters such as Australia we saw anti-Vietnam rallies and the rise of the counterculture in the ‘sandstone’ universities.

Radical politics and social change were very much the vogue in the late ‘60s early ‘70s providing a receptive background for a serious but conservative intervention into mainstream economic orthodoxy.

According to philosopher John Gray’s book review of “The Long ’68: Radical Protest and it’s Enemies” (New Statesmen 2018)

“Few of those that had been anti-capitalist in 1968 went on to embrace capitalism in any positive manner. But a cult of individuality, which co-existed among many 68ers with a theoretical admiration for collectivist economics, played a definite part in opening the way to Thatcher and Reagan.

Many revolutionaries assumed the year was only a prelude to an enormous social upheaval. In one sense, this proved to be the case. In the decades that followed, society was radically transformed in ways the 68ers had not imagined. Capitalism spread throughout the world and extended its reach into every corner of society. In Britain, the archaic self-governing universities against which students and their sympathisers in the faculty had revolted became subservient to market imperatives and government directives. Everywhere, the middle classes became more insecure even as their incomes increased”.

Concurrent with this social upheaval was the emergence of a significant economic dilemma. Western economies were confronted by the apparent failure of the then current economic orthodoxy – Keynesian demand management – to explain the concurrently prevailing high inflation and high unemployment or what came to be termed ‘stagflation’. Under the Keynesian paradigm, economic management made the targeting of full employment the primary indicator of success. The ‘stagflation’ of the 1970s shattered any illusions that the Phillips curve – the trade-off between unemployment and inflation – remained a stable and predictable policy tool for Western governments. This was a devastating blow to Keynesian economic credibility. However, it should be remembered that underlying this economic crisis lay a series of exogenous oil shocks and the collapse of Bretton Woods, all of which resulted in deepening economic instability. Events foretelling the demise of Gough Whitlam – the 1975 Australian constitutional crisis, also known simply as the Dismissal.

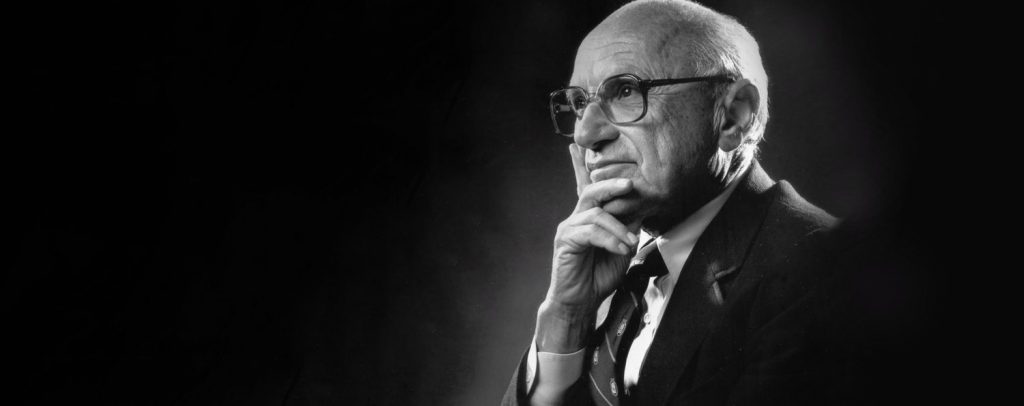

In view of these prevailing economic conditions, conservative political forces had mobilised an argument that the welfare state not only undermined capitalism but had inflationary and destabilising economic consequences. As politicians and policymakers cast around for solutions to the economic crisis, the conservative supporters of this new strategy thought ‘monetarism’, advocated by Milton Friedman in the US, seemed to offer an escape. This proved to be a failed strategy soon abandoned, and the wider neoliberal world view, as advocated by Hayek et al, took hold. This model took the form of a much-diminished role for the state, the deregulation of markets, tax reductions, privatization of national assets, suppression of trade unions.

And, significantly, inflation replaced unemployment as the central concern of economic policy makers.

By 1981 Friedman’s thirty-five years of laissez faire evangelism had established a new economic reality. The ascension of Ronald Reagan had moved the GOP fringe ideas about small government to the seat of American power. In 1980, a highly publicised TV program featuring Friedman, called “Free to Choose”, was aired by PBS. Of course, Friedman didn’t achieve this intellectual triumph alone. He had much of academe and an extremely well-funded political movement behind him. But he was the most prominent voice of that movement around the world. This attachment to the neoliberal faith by the current government is well illustrated when IPA lacky, Tim Wilson, held a copy of Friedman’s “Capitalism and Freedom” when being sworn into Parliament in July 2019

Explicitly influenced by the Mont Pelerin network the Conservative and Republican governments of the 1980s gradually introduced neoliberal policies radically changing the political economies of the US and the UK.

In the US, contrary to the Republican myth, the Reagan economy was a one-hit wonder. For Reagan’s Presidency was a failure. There was a boom in the mid-1980s, as the economy recovered from a severe recession. But while the rich got much richer, there was little sustained economic improvement for most Americans. By the late 1980s, middle-class incomes were barely higher than they had been a decade before and the poverty rate had risen. When the inevitable recession arrived, people felt a sense of betrayal – a betrayal that Bill Clinton was able to ride into the White House.

It should be of great concern to us all that the current Treasurer finds his support for such a narrative in a Republican shibboleth rather than evidence-based fact checking.

Thatcher’s policies, instituted in the 1980s and broadly pursued by subsequent governments, changed the economic and social outlook of the UK. However, in contrast to contemporary narratives of her ‘saving the country’, the neoliberal economic experiment has failed to deliver, even on Thatcher’s own terms.{an excellent re-assessment of Thatcher’s legacy can be found in the Cambridge Journal of Economics (2020)

If the myth is true, if it is the case that the adoption of free-market ideology improved the UK’s economic prospects, it is reasonable to suppose the rate of economic growth was greater after this adoption than before. However, the data undermine this supposition.

Annualised increase in real GDP per capita of post-war governments

| Government | Years | Annualised growth rate |

| Conservative | 1951–64 | 2.82% |

| Labour | 1964–70 | 2.22% |

| Conservative | 1970–74 | 2.59% |

| Labour | 1974–79 | 2.31% |

| Conservative | 1979–97 | 2.09% |

So, unsurprisingly, after eleven years in office and strongly assisted by a cooperative media, Murdoch and Conrad Black, Thatcher’s legacy was established. Her influence was to go well beyond her own party – it became the ruling consensus of future British governments. Once adopted by both parties, ‘market fundamentalism’ became the new macroeconomic orthodoxy.

Notwithstanding Thatcher’s landslide win in 1983, and a comfortable win in 1987, her popularity never completely recovered from the policy failures of her first few years. The Conservative share of the vote declined with every election she fought.

Neoliberal policies were later adopted by Bill Clinton, prodded by his ex-Goldman Sachs advisor Robert Rubin, announcing that “the era of big government is over” before going on to budget surpluses, institutional deregulation of financial and property markets, etc, – a modified version of the neoliberal agenda – leading ultimately to the 2007-8 GFC. And further echoed in the UK under Tony Blair and New Labour. Blair and his ideology, “what counts is what works”, was masked in the verbiage of Anthony Gibbon’s “Third Way”. Perhaps best described as ‘soft neoliberalism’, the model proved to be restrained neoliberal in terms of economic policy and moderately progressive regarding social policy.

To be fair, this more muted neoliberal worldview was not restricted to Anglo-America. A partial home was earlier to be found in Australia with the Hawke/Keating government which, though constrained in application, provided a ‘soft’ neoliberal template for Clinton and Blair. The Australian experience was noteworthy with the implementation of a prices and income accord – an initiative from the ALP and formalized with the labour movement embracing wage restraint. The introduction of the Prices and Incomes Accord, conceived by Hawke and ACTU Secretary Bill Kelty, had a chilling effect on union militancy with the labour share of GDP falling to 53% by 1988. It had recovered to about 55% by the time Keating departed in 1996. In the meantime, the neoliberal privatisation agenda had commenced with the CBA, CSL and Qantas being privatised. (In 1997, however, the Howard government debased the process when agreeing to extortion demands from Senator Harradine to buy his vote for the first tranche of the Telstra privatisation – a precedent which left a venal legacy.)

Despite an extraordinarily talented Hawke Cabinet, it was a most contentious period of labour history, according to history researcher, Elizabeth Humphrys. Taking the form of a social contract, Hawke’s Accord – with its commitment to markets, privatisations, and user-pay mechanisms – brought into Australia neoliberal activities that were elsewhere implemented only by the right. (How Labour Built Neoliberalism: Australia’s Accord, the Labour Movement and the Neoliberal Project” (2019)

A recent revelation from an official archive release lends even more intrigue to the period. During the 1970s, our future PM Hawke engaged in supplying the US with information about the ALP, the Australian government and the labour movement and was himself strongly influenced by this relationship with the US to abandon Keynesian economics and embrace neoliberal strategies. see The “Eloquence” of Robert J Hawke: United States Informer, 1973-79 (2021)

The Hawke/Keating legacy in terms of labour movement welfare is mixed. Hawke as ACTU president under the Whitlam government was decidedly confrontational, as PM consensus driven. Real politics is an unremitting master!

Unsurprisingly, such policies were later followed more strongly by the Howard government. Significantly, “market-based solutions” became the new conventional wisdom, the ‘go-to’ mantra for solving the big policy issues of our times.

Any suggestion that the world of economics is a value-free social science is ludicrous. Economic ideas are always rooted in ideological assumptions about how the economy and policy work. As we have seen, Keynesian ideas were widely (if not universally) accepted across advanced industrialized democracies in the wake of World War II. The late 1970s early 80s saw a shift in economic paradigms resulting in the West being enveloped in the neoliberal project – supply-side economic theory, privatisations, trickledown economics, deregulation, etc. – becoming the dominant school of economic thinking. This long march of neoliberal economics laid the groundwork underlying the GFC in 2007-8 and oversaw a rapid growth in toxic ‘financialisaton’.

The neoliberal economic policies that had dominated academia and dictated policy thinking for almost 30 years proved completely ineffectual in either predicting or addressing the GFC – the biggest financial debacle in the world since the Great Depression. It was indeed intriguing to observe politicians in authority during the crisis scamper back to Keynesian fiscal policy.

To be continued in next post – Part 2