It is clearly time to talk about NAIRU – the non-accelerating inflation rate of unemployment. The NAIRU is supposed to capture the sweet spot – the lowest level to which the unemployment rate can safely fall before inflation starts to accelerate.

Part 3 of 3 | Keynes, Pikketty and the the Pope identify the hegemonic issue

A critique in three parts –

1. Beware the ‘fundamentalist’ narrative

2. The growth of inequality, ideological crusades and zombie economics

3. Keynes, Piketty and the Pope identify the hegemonic issue

Nothing in economics is uncontroversial and NAIRU is no exception! Nevertheless, the concept is sufficiently mainstream that our Reserve Bank does regular calculations of NAIRU – these estimates are uncertain because it cannot be observed and are calculated using various economic models. The importance of estimating NAIRU is that it has become pivotal to the policy settings of both the RBA and Treasury. This is particularly so regarding the level of unemployment and consequently implications for wage growth and inflation.

It is worth noting that distinguished Australian economists Ross Garnaut and Justin Wolfers have in recent times urged the RBA to drive the employment rate down as far as possible – they both agree that this is likely to be closer to 3% than 5%. The point is that we don’t know what the NAIRU is until we get there, and any resulting inflation can be managed.

There is no reason, economic or social, for not genuinely making full employment the focus of our recovery – other than the suppression of wages.

Should that take place we have reversed, in terms of objectives, the paradigm change we let occur in the 1970s. With the existing high levels of unemployment (averaging 5.5% over the 5 years pre Covid) competition among employers for workers was minimal. It is no surprise that wages remained stagnant.

We currently have an interesting conflict between the RBA and, as we know, a politicised Treasury. The RBA guestimate’ is that Australia’s NAIRU is about 4.0%. On the other hand the Treasury’s updated modelling ‘guesstimate’ is 4.5-4.9%. It may appear close as a percentage but in the real world the difference is about 300,000 people in work. By driving down unemployment the labour market will get 21 to a point where it is so “tight” that competition for staff drives employers to start handing out bigger pay rises. Despite being the focus of several research papers,the relationship between immigration and wages remains inconclusive or at the very least patchy. As others have pointed out, the tentacles of high immigration level spread widely into many areas. Into housing accommodation, into traffic congestion and so on.

The Morrison government has so far resisted the RBA’s view. However, the closing of international borders has thrown yet another variable into the NAIRU mix. PostCovid, the immigration rate will again be an extremely contentious issue but, in the meantime, we might see the RBA’s objectives of annual wage growth approaching 3.0% with inflation in the target range of 2-3 percent – at least until the borders reopen.

Certainly, while borders are closed and immigration non-existent, we can theoretically expect the level of unemployment to fall to approximate the “natural” unemployment level with a concomitant boost to wages. However, there remains issues such as covid induced ‘lockdowns’ to be factored into the process and its effect on participation rates making unemployment data meaningless. Perhaps changes in hours worked remain the only reliable metric available. For an excellent analysis of NAIRU and its limitations, James Galbraith “Time to Ditch the NAIRU” (1997).

Such is the legacy of Frydenberg’s “inspiring” progenitors! Since 2008 most Western economies have been slowly returning to minimal economic growth, characterised by declining investment, declining productivity, wage stagnation,rampant inequality. In other words, ‘secular stagnation’ as identified by former US Treasury secretary Larry Summers in 2013!

When reviewing that history, it can be seen that economic ideas are always rooted in ideological assumptions about how the economy and policy work. Ben Clift’s cautionary words should never be far away – “The process by which economic theory is invoked in economic policy recommendation and rationalisation is inherently political.” Clift (2018).

The above is essentially a brief history highlighting some of the pivotal economic ideas which underlie the evolution of Western neoliberal capitalism since the Reagan/Thatcher periods of government. As we have seen, underlying Frydenberg’s rather hollow Reagan/Thatcher inspiration was his belief in neoliberal ideology with its fealty to small government, and the myth of trickle-down economics.

We have examined the genealogy of the Thatcher/Reagan dalliance, the resulting economic instability following the crucial shift in economic orthodoxy, we have noted the ascendancy of neoliberal rationality – where enshrined market principles have been transformed into ubiquitous governing principles.eg financial deregulation, privatisations, minimising government by defunding public institutions.22

In this regard, I’m reminded of that delightful vignette related by Mark Carney (exGovernor, Bank of England) when dining with the Pope at the Vatican –“Pope Francis pointed out that just as the grappa served after the meal was distilled wine—stronger in alcohol content than wine but without its many flavours and attributes—so the market was “distilled humanity”: concentrated self-interest devoid of everything else that makes us human. Your job, the pontiff told me and the other guests, is to “turn the grappa back into wine, to turn the market back into humanity.” [Carney (2021) “Values: Building a Better World for All”]

Carney avoids the intellectual separation of the economic from the social as he examines how economic values and social values are blurred under neoliberal economics – from a market economy to a market society in which “the price of everything is the value of everything”.

Following the GFC we saw a renewed but short-lived embrace of Keynes. It seems that Keynesianism remains the default policy driver for progressives around the world. And it should be noted that every time capitalism is in crisis even its strongest critics clamour for Keynes return. As leading Keynes’ critic Robert Lucas put it in 2008 “everyone is a Keynesian in a foxhole”.

Why does Keynesianism make so much sense to many on the “left”? Keynes himself was no radical, as Eric Hobsbawm remarked Keynes came to save capitalism from itself. Despite its evolution into several economic strands, at its core Keynesianism – the logic, the concepts and the politics – remains remarkably consistent and ideologically appealing to progressives. Economic remedies are understood as being socially fair, unemployment is given primacy, protecting the collective, civil society, accountable and a soft ‘dirigisme’. At its basic level, it is a

social philosophy that rejects unregulated free-markets, that budgets should be balanced, rent-seeking and favours a mixed economy – a case of economics engaging with society, in a word ‘civilised’! This locating of Keynes in the pantheon of macroeconomics and the intra-Keynesian debates are, however, far from straightforward.{ See Geoff Mann’s article in Foreign Policy mag (2019)}

Frydenberg’s exhumation of neoliberalism’s rather dubious couple led us to a fork in the road and the road chosen has taken Australia down a socio/economic rabbit hole, generating extreme political partisanship, culture wars, regressive social policies short-termism, income insecurity, tolerance of political corruption, a disengaged public, and, of course, inequality of wealth. All can be traced back to neoliberal governance.

We have witnessed the unedifying history of neoclassical economic thought which filtered out the socio/political components of economic life. Excluding values, ethics, power, inequality, leaving the mainstream school of macroeconomics as simply a scaled-back, value-free, carcass of selective economic “tools.” Turning grappa into wine it isn’t!23

The closed school of ”neoclassical” economics perpetuates itself in a handful of leading academic journals and in textbooks promoted at tertiary institutions – essentially a ‘protected’ workshop inaccessible to dissenters.But dissenters there are in abundance. We have seen the rapid growth of heterodox economics – an umbrella term covering diverse strands of substantive economic theories – plus the latest group of ‘heretics’, Modern Monetary Theory advocates now clamouring at the door.

It is evident that macroeconomics has undergone a serious evolution since the simplistic days of a Reagan/Thatcher. We have also seen how political parties conveniently interweave with evolving macroeconomic paradigms and policies. As for our fledging Treasurer, advice that “There are more things in heaven and earth, Horatio, than are dreamt of in your philosophy” would not be too patronising.

Unemployment certainly remains a key economic focus but following the 2008 financial crash the central political/economic critique shifted to ‘inequality’ – the new cause celebre for progressives and a critically unambiguous social issue.

Again, it is the ‘march of events’ – not debates – that creates the conditions for change. Perhaps an early precursor an be found in the so-called “Battle of Seattle”in 1999 protesting a new round of WTO trade negotiations. The protesters were later often mocked by critics as being rather silly and misguided. Interesting, in hindsight, that many of the protester’s concerns raised at the time have been proven right. We also witnessed the Occupy Wall Street in 2011, with the slogan “We are the 99%”. As distinct from the Seattle protests which were directed at globalisation, these protests were more narrowly focused on issues such as income inequality, the flagrant orruption of Wall St and the excesses of the finance industry. Privatising profits and socialising losses became Obama’s game plan. Interesting personal commentary by participant Molly Crabapple ”Ten Years AfterOccupy” NYRB (2021)

However, protests by social movements are not confined to marches by activists. The recent ‘populist’ events such as Brexit, the rise of Trumpism were achieved through established set of democratic principles governing those countries. But what I find particularly interesting is that most of the significant socio/political movements eg women’s suffrage, gay rights, civil rights (US), anti-war (eg Vietnam),etc were all decoupled from economic policy – with the exception of environmentalism. It has been my view for some time that the ‘progressives’ won the culture battles and the ‘market fundamentalists’ won the economic battle.

However, with the growth of obscene inequality, it now seems that the economic battle is far from over, these populist anti-globalisation episodes may yet have a long way to run – particularly regarding macroeconomic policy.

The importance of inequality and its consequences cannot be overestimated. This is not some secondary issue; it is probably the most significant issue we face in the first quarter of the 21st century. As Saul Eslake says – Inside Story (1917) –24 “It is one of the great paradoxes of globalisation of the past three decades, that although global inequality has declined, inequality within nations has increased. That is partly because the aggregate income gains delivered by globalisation have disproportionally gone to the middle classes in emerging economies (particularly in East Asia) and the top 1 per cent in both emerging economies and advanced economies, while the vast bulk of people in the poorest emerging economies (particularly in Africa) and the working and middle classes in advanced economies have gained very little, if at all.”

Without doubt the causes of inequality – both globally and within countries – are extremely complex. But there is one particular economic myth which needs to be dispelled viz the so-called ‘equality and efficiency’ trade-off encapsulated in the role of incentives. Essentially, the belief that companies and individuals require the prospect of high incomes to save, work hard and innovate. In crude terms, this provides the start-point for the fiction of ‘trickle-down economics. However, in recent years neither economic theory nor empirical evidence has been supportive of this alleged trade-off. Economists are now producing evidence showing why good economic performance is compatible with distributive fairness. Economists at the IMF produced empirical results showing that greater equality is associated with faster growth, both across and within countries. This is a striking finding – particularly because it comes from the IMF, an institution not known for heterodox or non-orthodox ideas.

In her speech at Davos in 2013, Christine Lagarde of the IMF stated – “Inclusive growth is certainly a top concern of policymakers. The message is resonating widely.

I was not surprised, therefore, to see that the World Economic Forum’s most recent survey puts “severe income disparity” at the very top of global risks over the next decade. Excessive inequality is corrosive to growth; it is corrosive to society.

I believe that the economics profession and the policy community have downplayed inequality for too long. Now all of us—including the IMF—have a better understanding that a more equal distribution of income allows for more economic stability, more sustained economic growth, and healthier societies with stronger bonds of cohesion and trust. The research reaffirms this finding.”

And, as we have seen, the establishment of Keynesian driven welfare economies after WW2 significantly moderated this growing inequality until it was overwhelmed by the political forces of neoliberalism in the form of Thatcher/Reagan and neoclassical economic policies. Neoliberalism ideology has proved to be more than applied neoclassical economics. As defined by essayist/author, George Scialabba –25 “Neoliberalism is essentially the extension of market dominance to all spheres of social life. In economic policy this means deregulation and privatizations. In culture it means untrammelled marketing and the commoditization of everyday life, it means consumer sovereignty, non-discrimination (which is after all economically irrational), and a restrictive conception of the public interest. In education, it means the replacement of the public for the private (i.e., business) support for schools, universities, and research, with a concomitant shift of influence over curriculum and research topics. In civil society, it means private control over the media and private funding of political parties, with the resultant control of both by business. In international relations, it means investor rights masquerading as ‘free trade’ and constraining the rights of governments to protect their own workers, environments, and currencies.”

This is the strength of neoliberalism, its capacity to permeate broad areas of society by being the ‘go-to’ solution for major issues encountered by right-wing governments. However, inequality has become the defining issue of the 21st century and the difficulty for neoliberal ideology is that it is the creation of the very economic system it promotes. In other words, the growth of inequality is endemic to the policy settings of neoliberal capitalism.

The evolution of neoliberalism has followed a tortuous route ending on a path leading inevitably to a plutocratic government underpinned by financialisaton and a rentier economy. We see the circle joined as we return to the Giles & Page research findings on neoliberal governance. What is particularly troublesome has been the shift of the financial sector away from investing in corporations that actually produce goods that are in demand towards investing in foreign currencies, derivatives and debt – a process decoupling finance from other parts of the economy. The concomitant to financialisaton has been the decline in secure employment and the shift in the path to financial security from earning and saving a wage to acquiring assets that appreciate in value.

When Kenneth Hayne’s report on banking, superannuation and financial services was delivered in early 2019, a contrite Morrison and Frydenberg promised to act on all of Hayne’s recommendations. For a while it seemed that the Liberals were prepared to enact some meaningful reforms on our pampered and bloated finance sector. But it went cold on economic reform when its mates, lobbyists in the finance sector, brought pressure on the government. Helen Bird of Swinburne Law School, writing in Inside Story examines the ephemeral government response Haynes’s recommendations (very depressing reading unless you are a finance executive or mortgage broker!). The conventional wisdom within neoclassical economics is ‘that the purpose of government policy is to correct market failures”. In the case of the financial sector’s failures, it is the consequence of policy of the government. As Polanyi has pointed out, at their core, markets are structured by governments.26

Rising economic inequality was a major cause of the financial crisis. This is the conclusion of an emerging body of research into the links between inequality and the growth in scale and influence of the financial sector. (New Economic Foundation (2014)} “It is becoming clear that financialisaton is linked with rising inequality. Led by a dismantling of the controls over financial flows, the finance sector has been the main component of a decisive shift in the share of gross domestic product (GDP) towards capital and away from labour. Within the shrinking

wage share, huge increases in income for top earners, particularly in the finance sector, have left even less for the other 99%. Meanwhile, barely constrained expansion of credit and the consequent relentless rise in asset prices have concentrated wealth in fewer hands. The process is selfreinforcing because increasing wealth accrues both higher income returns and greater political power.”

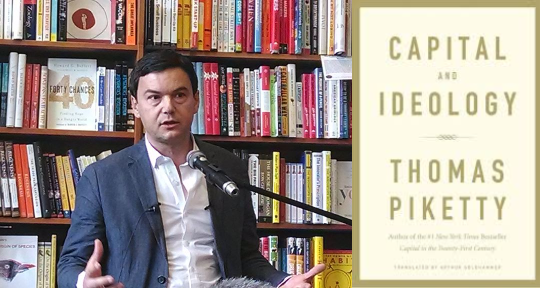

This is the doorway the French economics professor, Thomas Piketty, stepped through in 2013 with the publishing of “Capital: in the Twenty-First Century”.

The reception to “Capital” (often referred to as “C21”)was tumultuous – ‘groundbreaking’, ‘explosive’, ‘a blockbuster’, ‘deserves a Nobel Prize’ and so on. The New York Times said, “Remarkably for a book on such a weighty topic, it has already entered the NYT best-seller list”. It was a massive book (696 pages in the English translation), packed with economic analysis of inequality and growth and full of charts. The book’s central tenet is that wealth grows faster than economic output concentrating capital (including the income it produces) in fewer hands. Hence the famous formulation, r > g where ‘r’ is the return to capital and ‘g’ the overall growth rate.

According to the New York Times, “Capital” is “a return to the kind of economic history of political economy written by predecessors like Marx and Adam Smith”. An observation by Lawrence Summers (a doyen of US mainstream economists) seemed to resonate with many readers “Piketty writes in the epic philosophical mode of Keynes, Marx, or Adam Smith rather than in the dry technocratic prose of ost contemporary academic economists.” It was reviewed or debated everywhere, from the print media to the blogosphere. However, much early commentary addressed the minutiae – the methodology, the theoretical framework, etc.

Unsurprisingly, the book was strongly attacked in the Financial Times by journalist Chris Giles for example. The far-right Cato Institute in the US even published a book “Anti-Piketty: Capital for the 21st Century” casting Piketty’s tome as a threat to civilisation.

Perhaps, however, the greatest rebuke of Piketty was the deafening silence it met within the mainstream economics profession. It seems that the ‘narrowness’ of neoclassical macroeconomics, as mentioned earlier, is the explanation of this defensive stance. Particularly its analytical failure to consider social values, ethics, power and, of course, inequality in its modelling. Capitalism needs to be understood27 as a socio-economic system, not an economic structure defined in terms that can be mathematically modelled. Maximising utility, homo economicus – are concepts illustrative of the unreality of much neoclassical economic theory.

In many ways the substance of such critiques of Piketty are unfortunate, not because these points are unimportant, but they seem to miss the fundamental focus.

The critical issue of ‘inequality’ that Piketty exposes goes to the very heart of contemporary liberal capitalism.

The arrival of “Capital in the Twenty- First Century” did draw much commentary but it was the eminent US economist, Paul Krugman, who captured the essence when he wrote that C21 “will change both the way we think about society and the way we do economics”. He makes the claim in the excellent set of studies “After Piketty: The Agenda for Economics and Inequality” – a collection of essays focused on the arguments and consequences of C21. The concluding paper, by Piketty, argues that his work seeks to “reconcile economics with the broader social sciences”. Certainly, a very worthy and important goal!

However, like much of the commentary about inequality, the book broadly rests on an implicit moral claim: that excessive wealth concentration violates an intrinsic sense of fairness on which a just society depends. A theological issue of immense importance in a liberal democracy.

Confronting growing inequality is surely a key concern for whatever replaces neoliberal capitalism in the West.

In the meantime, we need to return to where we started – the future of the state. Despite evidence to the contrary, Frydenberg’s exhumation of Reagan/Thatcher reflects the ‘small government’ dogma largely accepted as doctrine by most politicians if not the public. Of course, economics alone can’t solve all Society’s problems, but it can assist us in understanding in a more nuanced way the inherent strengths and weaknesses of governments, markets and civil society.

We must wait and see the impact of the Covid pandemic – both domestically and globally – and whether a new normal awaits us on the other side. But there can be little doubt that the ‘state’ has grown in esteem and stature – almost the inverse of our political leaders whose limited capacity for leadership became so obvious.

As a matter of record, the Morrison government is now not only the biggest spender in Australian post-war history but also Australia’s biggest taxer. Not surprising, perhaps, given the record profits of the big iron ore miners, higher LNG, oil, gas and coal prices. Roughly in the order of 28% of GDP for the June quarter.If the pandemic does eventually provide a force for change in Australian governance, a transition to the new normal will need a recognition of neoliberal failings as a socio/economic system, the crushing of rentier financialisaton, an

immediate strengthening of our anti-corruption laws, a re-engagement of the electorate with politics, and an enhanced recognition of the role of the state.

The Australian economy is dominated by service-based businesses, constituting around 70% of GDP. Exports are heavily skewed towards the resources sector, with28 primary products such as minerals, metals, and coal constituting 64% of all Australia’s exports. With a manufacturing sector in this country at less than 6% and the services sector at 70% of GDP it should be of no surprise when John Hewson supposedly quipped “the entire country is basically sitting around serving each other cups of coffee”

Meanwhile the Morrison government continues to foster a property Ponzi as an innocuous ALP ejects negative gearing from its electoral platform. Even Philip Lowe, Reserve Bank Governor, acknowledged the problem of affordability and the associated problem of high household borrowing, but he did not see it as the bank’s responsibility to dampen demand through raising interest rates or imposing regulatory curbs on lending practices.

If there is a single factor depicting our industrial history, it is Australia’s overwhelming reliance on the export of unprocessed raw materials to drive our growth and prosperity. This has harmful consequences such as the Dutch Disease driving up exchange rates and destroying what is left of our industrial base. The sad truth is that we sustain our ‘first-world’ lifestyle with a ‘third-world’ industrial structure.

This was the message of the Economic Complexity Index (ECI) – a broad measure of the production characteristics of countries and was developed by economists at Harvard and MIT to explain an economic system as a whole and to identify the knowledge accumulated in a country’s population and expressed in the country’s industrial output.

In 2019 the ECI ranked Australia at the bottom of all OECD nations and ranked Australia as 93rd out of the 133 countries analysed. Australia ranks alongside Senegal (92nd), Uganda (91st), Pakistan (94th) and behind countries like Guatemala (79th) and Albania (78th).

In today’s world, the theory of comparative advantage like many economic concepts has become antiquated and irrelevant while today’s world has seen a manufacturing transformation.

After decades of market fundamentalism industrial policy is back. A new industrial revolution encompassing robotics, artificial intelligence, bioengineering and data analytics. Under this process, manufacturing is not just a vertical industry sector but also a horizontal enabler of technological innovation and change across future industries. Industrial policy must also address the failure of the private sector and financial markets to direct sufficient investment funds to critical sectors and technologies. Eminent economist, Mariana Mazzucato has in many ways led the way. Her work challenges orthodox thinking about the role of the state and the private sector in driving innovation and how economic value is created, measured, and shared. See her ‘The Value of Everything’ (2018)

However, with our PM absconding from his leadership role in our Federation, he has placed the future of our centralised government (the state) in jeopardy. By doing so, our ‘absentee’ leader has inadvertently laid bare a shift in power between levels of government in Australia. As Alan Kohler observed, “The federal government runs29 external affairs while domestically the nation is now a series of fiefdoms run by warlords (premiers).”

Perhaps a short-term aberration, with the Federal government in control of the purse strings such an arrangement will inevitably, in time, return to a more centralised form.

Without question, Australia today is a dismal caricature of a nation that has lost its way. Sadly, a country where the lowest common denominator is ‘good enough’; where political corruption is tolerated by a disengaged and detached electorate; where a duplicitous, secretive, boorish Prime Minister manages a mean, tricky, and

vindictive government. Such is the ‘lucky’ country!

This essay, prompted by Frydenberg’s exhumation of Reagan and Thatcher, has at its core an exhortation to revitalise the ‘state’ in a future social compact. Australia has been poorly governed virtually since the turn of the century : dominated by short-termism, electoral politics, and apathetic socio/economic governance – particularly during the last decade.

The essay highlights three core themes:

- the economic importance of the ‘state’ in a liberal democracy

- the political power of economic ideas – a key underlying element and

- the ideological interweaving of governments between economic paradigms.

To summarize: we saw the diffusion of Keynesian ideas post-WW2 until the late 1970s, followed by the infliction of the Hayekian neoliberal world until the GFC in 2008, followed by what could be best described as economic anomie since that time, drifting toward the hegemony of heterodox economics.

In a memorable phrase, Keynes once observed that “the ideas of economists and political philosophers, both when they are right and when they are wrong, are more powerful than is commonly understood”

Throughout the history of economic thought, government has long been regarded as unproductive, a spender and regulator but not a value creator. We are told government does not create value, it simply facilitates its creation. Apart from fixing ‘market failures,‘ government should only intervene in the economy if there is a problem otherwise focus on getting conditions right for business. While such dogma is a conventional view of government’s role, the history of capitalism reveals a less simplistic story. A distinguished Hungarian economist/anthropologist, Karl Polyani, argued that markets were far from natural creations rather they were the result of policymaking by the state. Polyani has belatedly gained recognition around the world as one of the most important thinkers of the 20thcentury. Polyani traced and analysed the long history of domestic and international markets showing that the capitalist market – the one we study in economic classes – was actually created by the state.

Governments don’t distort the market, rather the market is the state’s creation. Starkly put – no state, no market!

This institutional view of markets relationship with government contrasts sharply with the current orthodoxy found in neoclassical economics. As a discipline, economics emerged largely to assert the productive primacy of the private sector.30

On the other hand, Keynes proved to be of key importance in showing the dynamic role of public expenditure. Part of the problem is that the argument for fiscal spending is tied to counter-cyclical demand management with too little creative thinking about how to manage the economy in the longer run. Portraying the government as a more active value creator can eventually modify how it is regarded. Often governments see themselves as facilitators of a market system as opposed to co-creators of wealth.

What is required is a deeper understanding of public value, a term almost lost in economics today. In this new world, according to Mariana Mazzucato, (2018) – “There would certainly be no more talk of the public sector interfering with or rescuing the private sector. Instead, it would be widely accepted that the two sectors, and all the institutions in between, nourish and reinforce each other in pursuit of the common goal of economic value creation. The sectors interactions would be less marked by hostility, and more infused with mutual respect.”

At some time in the future a new world awaits us – perhaps not very likely if the stagnant Morrison government is still in residence! We will end these essays with the inspiring words of novelist Arundhati Roy in the Financial Times (2020) as to what the world should do next when finding a new normal – “Historically, pandemics have forced humans to break with the past and imagine their world anew. This one is no different. It is a portal, a gateway between one world and the next. We can choose to walk through it, dragging the carcasses of our prejudice and hatred, our avarice, our data banks and dead ideas, our dead rivers and smoky skies behind us. Or we can walk through lightly, with little luggage, ready to imagine another world. And ready to fight for it.