“Frydenberg exhumes Thatcher and Reagan”, so the Murdoch press gleefully extols.

Part 2 of 3 | The growth of inequality, ideological crusades and zombie economics

A critique in three parts:

1. Beware the ‘fundamentalist’ narrative

2. The growth of inequality, ideological crusades and zombie economics

3. Keynes, Piketty and the Pope identify the hegemonic issue

In economic emergencies ‘politics’ drives economics. The GFC was no exception: fiscal stimulus and quantitative easing measures became the predominant response of both the UK and US governments and their central banks – essentially Keynesian in nature. Meanwhile, in the US, academic struggles were taking place between the two primary macroeconomic schools – the ‘freshwater’ school descended from Milton Friedman at the Chicago University and the ‘saltwater’ school descended from Keynes and based at MIT, Princeton and Harvard. At its simplest level, the struggle was between “budget deficits always bad” as opposed to “deficits are beneficial in a slump”. That, of course, does a disservice to the nuances of the various arguments, but it reflects the endgame of the two schools.

What was striking is that nobody saw the financial crisis of 2008 coming! It is inconceivable but nevertheless true that despite data to the contrary eg housing bubbles, mortgage issues, mainstream economists believed their mathematical models told them that housing bubbles just don’t happen, markets are stable and always clear ie efficient and effective. Obviously, it was a case of purity trumping reality!

As mentioned above, following the 2008 financial crisis we witnessed, much to the chagrin of the ‘freshwater’ school, a resurrection (albeit short-lived) of Keynesian fiscal policy. We witnessed the failure of the ‘efficient-market hypothesis’ which underpinned the policy direction of the ‘freshwater’ school. The critiquing of the failed orthodoxy gathered apace with the growth in heterodox theories. see ‘Consensus, Dissensus, and Economic Ideas: Economic Crisis and the Rise and Fall of Keynesianism’ Farrell& Quiggin (2017), ‘The IMF and the Politics of Austerity’ Ben Clift (2018)

But post GFC, the centrality of unfettered markets remained. Serious research into how markets are created and operate would have seemed a good start. As Karl Polanyi pointed out many years ago, so-called ‘free’ markets are simply constructs of economic theory and government intervention – artificial creations resulting from public policy and regulation. The point being that governments structure markets in very fundamental ways – ways that have an enormous impact on income distribution.

A favourite British political adage holds that ‘all political lives end in failure’, but few failures are quite as complete, or lonely as David Cameron – with the Brexit referendum being his final act of ineptitude. “We should use this crisis of capitalism to improve markets, not undermine them.” (New Statesman 2012)

A weak, under-achieving Prime Minister with highly questionable values!

In the UK under David Cameron, initial fiscal expansionary policies were soon replaced by austerity measures. The policy of “expansionary austerity” became the new darling of academic research. Though many research papers were subsequently written e.g., IMF, Blyth (2013) which ultimately led to the theory being discredited – but not before much economic damage had occurred – particularly in the UK and the EU. See ‘The Myth of Expansionary Austerity’ (2019)

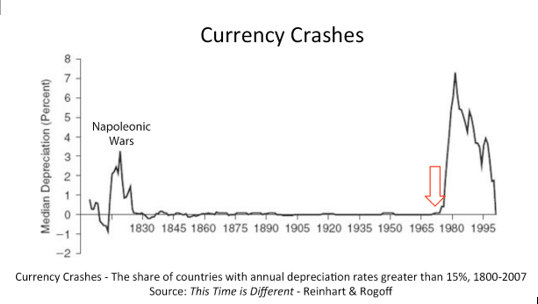

In the EU, post-GFC recovery was in disarray, culminating in the bizarre treatment of Greece. The failure of Maastricht treaty of 1992 to recognise individual national differences within the eurozone and the application of a rigid fiscal-policy framework proved insurmountable. Consequently, we were forced to witness another Greek tragedy. In this case a modern one, largely a consequence of the German obsession with inflation – derived, ostensibly, from long-held memories of the hyperinflation encountered by the Weimar Republic in the early 1920s.

The financial crash of 2008 was the most severe since that of 1929. But, as economists Reinhart and Rogoff have pointed out (in hindsight), since most countries carried out financial deregulation and liberalisation in the 1970s and 1980s, there was a huge increase in banking crises. The IMF had recorded 124 systemic bank crises and 63 sovereign debt crises in the period 1970 to 2007.

As we have seen, underlying Frydenberg’s farcical Reagan/Thatcher inspiration was his belief in neoliberal doctrine with its fealty to small government.

When reviewing that history, it can be seen that economic ideas are always rooted in ideological assumptions about how the economy and policy work. Ben Clift’s cautionary words should never be far away –

“The process by which economic theory is invoked in economic policy recommendation and rationalisation is inherently political.” Clift (2018)

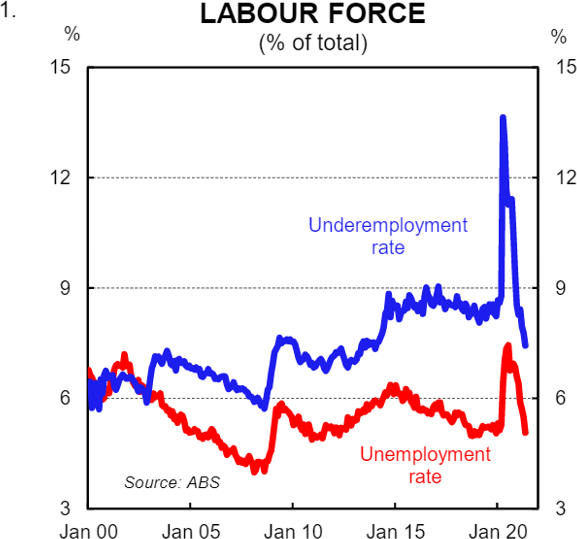

Closer to home and contrary to current government rhetoric, Australia’s economy performed poorly from the GFC through to the Covid-19 pandemic – the period was appropriately termed ‘Dog Days’ by Ross Garnaut (2021) Unemployment and underemployment remained high – well above the rates in other developed countries that had suffered greater damage from the GFC. Additionally, wages stagnated, with slower growth in productivity than the rest of the developed world.

According to the Productivity Commission, “(For Australia) The decade ending 2019‑20 was the worst decade of growth in 60 years, and even if the last year of growth is excluded then this nine-year period still compares unfavourably to past decades.”

Yet the government boasts about Australia’s miracle post-Covid economic recovery. No mention that the recovery is from the low base of our poorly performing pre-Covid economy.

Supply-side economics remained dominant government policy until Covid-19 emerged. Then, in late April 2020, Frydenberg turned abruptly away from years of Coalition rhetoric demonising budget deficits and, seemingly, embraced fiscal expansionary policy. Suddenly ‘debt and deficit’ was jettisoned, and public debt embraced We witnessed Frydenberg’s Damascus moment – from exhumations to epiphanies. From Reagan/Thatcher to Keynes in an instant. A politically driven capricious Treasurer!

But Frydenberg (and Morrison) have always been political pragmatists, never prisoners of past ideology, recognising that aspirational individualism in Australia was more myth than reality. As historian John Hirst argued, “Our whole history is one of reliance on the state, strong regulation, and mass compliance.” Our experience with occasionally lengthy hard lockdowns during the Covid-19 crisis, in the face of immediate threats, suggests we are very obedient to authority and have strong underlying belief in the government’s role in solving our problems.

This cultural characteristic of risk aversion enabled the locking down of states or cities to become a popular political tool exercised by all political parties (even NSW, grudgingly) When referring to a recent PwC survey indicating high trust in government, academic Glyn Davis said, “the survey confirms what we see around us – that in a crisis people look to government at all levels.” Note that all these major surveys took place before the Federal government’s bungled vaccine roll-out commenced.

Frydenberg’s epiphany did, however, expose the shameless hypocrisy of Coalition governments, having for many years spun the ‘debt and deficit’ line as the most important task of economic policy. It was an absurd line but a convenient one when delivered to a gullible electorate.

Government funding in an economic crisis is usually divided between ‘rescue’ spending and ‘recovery’ spending. In the Australian context, ‘rescue’ spending refers primarily to actions associated with the Jobkeeper policy, initially advocated by the ACTU. Jobkeeper introduced a form of wage subsidy which proved reasonably successful but only to the limited extent of its application. Unfortunately, its flawed design left too many people falling through the cracks. Universities, the arts community, the gig economy etc were all simply abandoned. This has been a moment of truth about the way Australia works, and why it doesn’t really work at all for millions of people. The ideological discriminatory application of Jobkeeper highlighted a mean and tricky government. Contrast the government enthusiasm to institute the callous “Robotdebt” scheme with the abject failure to reign in blatant corporate theft by businesses – estimated at $12.5 billion – associated with the Jobkeeper policy! And now the government has the temerity to target any employee who may have been overpaid under the same program.

However, spending associated with the ‘recovery’ or ‘stimulus’ phase requires a different set of decisions, typically a binary choice. Do we spend on old dirty industries who will most likely leave us with stranded assets, or do we go with more contemporary policies which can deliver a better result for both the economy and the environment? It is instructive that a new study to be published in the Oxford Review of Economic Policy, assessing global stimulus efforts, says that of the 20 countries included in the study, Australia was the only country backing fossil fuels.

The ‘gas led’ economic recovery mantra by Morrison is little more than an obvious ploy to embed a gas market in the economy – a honey pot for rent seeking lobbyist/donors to the LNP. What is even more damning of the Government’s gas plan is that there are many alternate stimulus possibilities that would create far more jobs and environmentally friendly investment returns than fossil fuels. For example, the Grattan Institute proposal or the excellent “Million Jobs Plan” developed by the think-tank Beyond Zero Emissions and modelled by economist Chris Murphy.

This is not to say that gas industry expansion, despite its lack of longer-term efficacy, is an inherently bad short-term policy initiative – there may be a transitory role for gas but not if its viability requires government investment in the energy market and the country being left with high-cost stranded assets. And it is certainly not the legitimate role of government to be subsidising gas projects at the behest of lobbyists and rent seekers.

So, gird your loins (figurately) for a repeat gas industry rip-off!

Sadly, this Government’s narrow view squanders the opportunity provided by the pandemic. As the trite but nevertheless sage advice suggests “You never want a serious crisis to go to waste”.

Remember, it is only two years ago that Frydenberg stood in parliament proclaiming “the first surplus in twelve years and the first repayment made on Labor’s debt” while talking up the government’s alleged economic management skills. It was a moment of hubris, completely ignoring the economic reality of the Dog Days it was mired in – wages stagnating, floundering productivity, and minimal interest rates .

The Treasurer emerged from the pandemic with an epiphany and a new mindset. Suddenly, unemployment returned to centre stage with inflation restraint being thrust to the background.

Consequently, with monetary policy being helpless (interest rates at zero lower bound), fiscal policy would continue to do the heavy lifting. However, with the resurrection of unemployment as the significant measure of economic performance, stagnant wages finally had to be positively addressed.

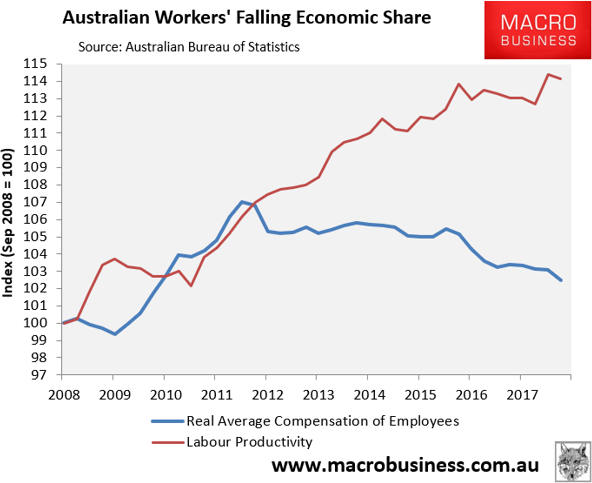

Two years ago, the long-running debate over the causes of wage stagnation was partially answered, when Finance Minister Matthias Cormann described policies suppressing wage growth as “a deliberate design feature of our economic architecture”. A rare slip from an otherwise secretive, mendacious government!

We now know that since neoliberalism emerged in the late 1970s, both the architecture of labour market regulation and the discretionary choices of Federal governments have been designed with the objective of suppressing wages.

The success of those policies is evident below.

Reducing this so-called “real wage overhang” became the focus of macroeconomic policy throughout the late 1970s and 80s

This decline in the wage share of national income has been variously blamed on technology, Chinese imports, artificial intelligence, etc. However, a more realistic explanation began with the breakdown of the Bretton Woods system of fixed exchange rates and associated oil shocks. As a consequence, both wages and prices rapidly accelerated – a wage /price spiral – and when inflation slowed down wages share of GDP had risen to 62%. That purported ‘overhang’ was gradually eliminated by the 90s – mainly through changes to industrial legislation – most of which attacked unions and weakened the bargaining power of labour. Of particular importance at the time was the Fraser government proceeding to introduce changes to the Sections 45 of the Trade Practices Act – the banning of secondary boycotts

These changes to industrial law, grossly weakened the capacity of unions to strike and negotiate wage increases. The introduction of the Prices and Incomes Accord, conceived by Hawke and Bill Kelty, had a chilling effect on union militancy with the labour share of GDP falling to 53% by 1988. It had recovered to about 55% by the time Keating departed in 1996. In the meantime, the neoliberal privatisation agenda had commenced with the CBA, CSL and Qantas being privatised.

Research suggests three leading explanations for redistributive trends in factor shares across industries –

- Market power: A decrease in labour bargaining power

- Technology: A decrease in the cost of capital (or higher capital-augmenting technological change (e.g. automation) will lower the labour share of income.

- Globalisation: A decrease in the cost of foreign labour relative to domestic labour will lower the domestic labour share

To a significant extent, only the governments of nation-states are capable of regulating market power, according to Harvard Professor, Dani Rodrik {NYT Sunday Review Sept (2016)}

In Australia, the dilution of bargaining power enabled a fundamental restructuring of power balances in the labour market. This restoration of business dominance by a neoliberal government, corporate elites and their allies was a core component of the strategy and reflected the neoliberal economic ascendency in this country.

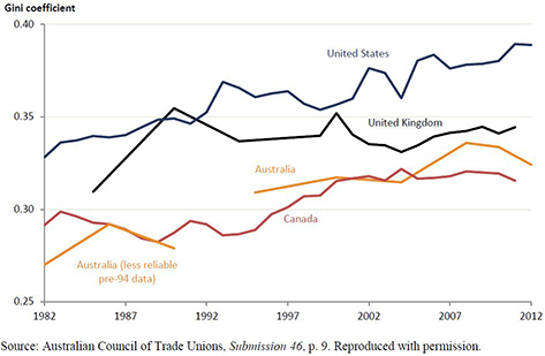

Early in the 1970s, Australia was ranked as one of the most egalitarian economies in the world. But the late 70s early 80s saw the implementation of neoliberal labour market policies leading to the dramatic redistribution of factor income away from labour to capital. The Gini Coefficient – the internationally accepted summary measure of inequality – now ranks Australia a lowly 23rd amongst OECD nations keeping company with, unsurprisingly, our Anglo-American neoliberal cohort.

According to the OECD (2011) increasing Income inequality followed different patterns across the OECD countries over time. It first started to increase in the late 1970s and early 1980s in some English-speaking countries, notably the United Kingdom and the United States. By 2017 the labour share of GDP had reached its lowest level in 60 years.

Prior to COVID-19, inequality in Australia in terms of income and particularly wealth, was extensive. Those in the highest 20% by household income had six times the incomes of those in the lowest 20%. Whilst average wealth in Australia was relatively high, it was distributed extremely unequally – those with the highest 20% of wealth had 90 times the wealth of those with the lowest 20%.

Gini coefficient for equivalised disposable household income in Australia, the US, the UK and Canada.

In the contemporary scene, we see a suite of government policies suppressing wages including public service wage freeze, inaction on wage theft and underpayments, opposition to increases in minimum wages, supporting a reduction in penalty rates, stacking the Fair Work Commission, an employer-friendly High Court. But regulating labour supply through immigration and temporary work visas has been a key tool employed by the government to suppress wage growth.

The progressive thinktank, the McKell Institute, recently released a report analysing the slowdown in the growth of average weekly earnings since the Coalition regained power in 2013. Wages grew by 1.0% in the period 2000 – 2013 compared to 0.4% in the period 2014 – 2020.

But apart from the decline in union membership and oppressive legislation, the most critical factor causing wage stagnation has been disproportionate immigration – particularly temporary visas – and its impact on the level of unemployment! An issue of problematic research!

Wage stagnation is not a uniquely Australian phenomenon, nor rapid gains at the top. French economist, Thomas Piketty, estimated that the share of total income accounted for by the top1% of earners has doubled from 8% in 1979 to 18% in 2015 – while the share of the top 0.1% had quadrupled from 2% to 8% over the same period.

As Harvard economist, Benjamin Friedman, said in “The Moral Consequences of Economic Growth” (2005)

“ the value of arising standard of living lies not just in the concrete improvements it brings to how individuals live but in how it shapes the social, political and ultimately the moral character of a people”.

Maybe life under neoliberal capitalism is really a zero-sum struggle!